- #Energy & Climate

- #Europe

- #Global Issues

► The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and subsequent `sanctions war’ between Russia and OECD countries – but particularly Europe and the United States – have resulted in a major increase in all energy prices in general and particularly natural gas prices.

► This will create problems and extra costs, particularly for European refineries and shortages of some oil products, principally diesel fuel. But the major problem – and the centre of the energy crisis in Europe – concerns natural gas supplies and prices.

► The most immediate consequence of this crisis is the very substantial increase in European LNG imports as a replacement for Russian pipeline gas. In 2022, the main impact on Asian countries has been drastically reduced affordability and therefore LNG imports, principally in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India.

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and subsequent `sanctions war’ between Russia and OECD countries – but particularly Europe and the United States – have resulted in a major increase in all energy prices in general and particularly natural gas prices. It has also resulted in a severe shortage of natural gas in Europe. Most European countries have implemented a phase out of Russian coal imports, and phasing out Russian crude oil and products is under way. This will create problems and extra costs, particularly for European refineries and shortages of some oil products, principally diesel fuel. But the major problem – and the centre of the energy crisis in Europe – concerns natural gas supplies and prices.

The European Natural Gas Supply Crisis

Over the past decade, natural gas supplies from Russia have accounted for one third of European gas demand. Following the invasion, a combination of:

- refusal by some European countries to continue to import Russian gas;

- Russian demands for gas supplies to be paid for in Roubles (rather than Euros);

- progressive reduction and eventual complete interruption of supplies through the Nord Stream pipeline

have resulted in Russian pipeline supplies to European Union (EU) countries reducing to around 15% of their normal levels. (Flows to Turkey through both Turk Stream and Blue Stream pipelines have remained unaffected.) In November 2022, the only pipeline flows which were operational were around 35-40 mmcm/d through Ukraine and 30 mmcm/d volumes via Turk Stream to Greece and non-EU Balkan countries. The ongoing conflict means that flows through Ukraine could be interrupted at any time. Russian LNG has continued to flow to EU countries (but not to the UK) and although this could also be impacted – either by EU or Russian sanctions – the consequences would not be as serious as further reductions of pipeline supplies.

To compensate for the loss of Russian gas, many countries are rushing to install floating LNG storage and regasification units (FSRUs) in time for the winter season. The key country here is Germany where six FSRUs have been ordered and the first three should be operational around the end of this year or the beginning of 2023. In the Netherlands, two FSRUs began operating in September, and others in France, Poland, Greece, and Finland/Estonia should be in operation by the end of 2023.

The EU also introduced a new gas storage regulation requiring member states to fill their storages to 80% of capacity by November 1, 2022. In reality by November, due to mild temperatures, overall EU storage levels were already at 95% (a higher level than the previous year). However, Europeans are already projecting how much gas will remain in storage in March 2023, particularly if the winter is cold, and if Russian pipeline supplies are completely interrupted. As long as winter 2022-23 is not too cold, Europe may have sufficient storage to maintain gas supplies without exceptional measures such as power outages and rationing. However, with the likelihood that Russian pipeline gas supply to EU countries will not increase from current levels (and may decline to near-zero), very low storage levels in Spring 2023 would create major difficulties. A general view is that if storages are more than 40% full by April 1, 2023 (the end of the European winter), it will be possible to refill storages in time for winter 2023-24.

The European Natural Gas Price Crisis

After the decade of the 2010s when internationally traded gas and LNG prices were largely in the range of $5-10/mmbtu, the past three years have seen prices move through two extreme market cycles. During 2020, natural gas and LNG prices reached historical lows below $2/mmbtu due (largely) to a combination of the Covid-19 recession and global oversupply of gas and LNG. For most of 2020, the JCC oil-indexed price (the main LNG price in north east Asia) was significantly above European levels (as it had been for much of the 2010s). Prices began to rise at the end of 2020 as European and Asian economies recovered from recession, and Gazprom first reduced and then eliminated spot and short term gas sales by the end of 2021. In the second half of 2021 and into 2022, European prices and the JKM spot price spiralled upwards to historically high levels of $20-30/mmbtu, while JCC and US Henry Hub-related prices also rose but much more slowly and a substantial gap opened up between these two groups. Following the Ukraine invasion, European gas prices spiked again and from June 2022, the progressive reduction of Russian pipeline exports to Europe, and intense government-directed purchasing of gas to ensure high storage levels for the coming winter, caused prices (particularly at TTF) to increase to even more extreme high levels of $40-70/mmbtu.

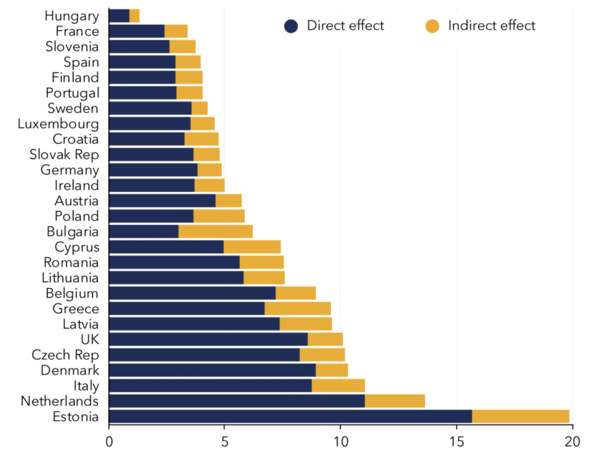

Figure 1. Increase in Household Costs Due to Energy Price Increases (2022)

Source: Europe Must Address a Toxic Mix of High Inflation and Flagging Growth (imf.org)

Figure 1 shows how this crisis has impacted on household bills in Europe. Most households have seen an increase of 5-10% in the costs as a result of energy price rises; for businesses and especially energy intensive sectors such as chemicals, steel and ceramics, the increase has been much greater. As a result, governments are having to provide subsidies of tens of billions of Euros (and for larger countries in excess of €100 billion). These are huge sums of money for economies which are still recovering from the COVID pandemic.

Possible implications for North East Asia

The most immediate consequence of this crisis is the very substantial increase in European LNG imports as a replacement for Russian pipeline gas. In 2022, the main impact on Asian countries has been drastically reduced affordability and therefore LNG imports, principally in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. Another impact has been the purchase by European companies of almost all available FSRUs which south and south east Asian countries had been intending to acquire. So far the impact on north east Asia has been minimal but this is mainly because, due to economic conditions, Chinese LNG imports have fallen for the first time in many years.

The crisis in Europe has created an extremely tight global LNG market. On the supply side, this will not change significantly until major new LNG projects – from Qatar, the US and East Africa – are brought onstream in 2026-27. However, it is possible that demand reduction caused by a combination of recession and very high gas (and electricity) prices will bring global supply and demand into balance earlier. However, the main consequence for north east Asia is that for the period up to 2026/27, European buyers can be expected to compete aggressively for available LNG supplies, potentially bidding up spot and short term prices especially during the winter season. Even after this very tight supply period finishes European buyers, particularly in north west Europe which was historically highly dependent on Russian gas, will remain more active global competitors than before the crisis. For north east Asian this is likely to be to the enduring consequence of the current crisis.

Jonathan Stern founded the OIES Gas Research Programme in 2003 and was its Director until October 2011 when he became its Chairman and a Senior Research Fellow, he became a Distinguished Fellow in October 2016. He is honorary professor at the Centre for Energy, Petroleum & Mineral Law & Policy, University of Dundee; fellow of the Energy Delta Institute and a Distinguished Research Fellow of the Institute of Energy Economics, Japan. His most recent papers published by OIES in 2020 and 2022 are: Measurement, Reporting, and Verification of Methane Emissions from Natural Gas and LNG Trade: creating transparent and credible frameworks; and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from LNG Trade: from carbon neutral to GHG-verified.