- #Europe

► Do symptoms of contestation of the international order necessarily call for a “global” answer - likely to alienate the Global South – and how can a global security architecture adapt to local threats (such as grey zone situations and those intertwined in regional politics)?

► The Asian partners have to be clear-eyed about the fact that, rather than proving an avenue for more defense cooperation between them, it may preclude any progress in indigenous strategic culture, let alone regionally-owned security architecture.

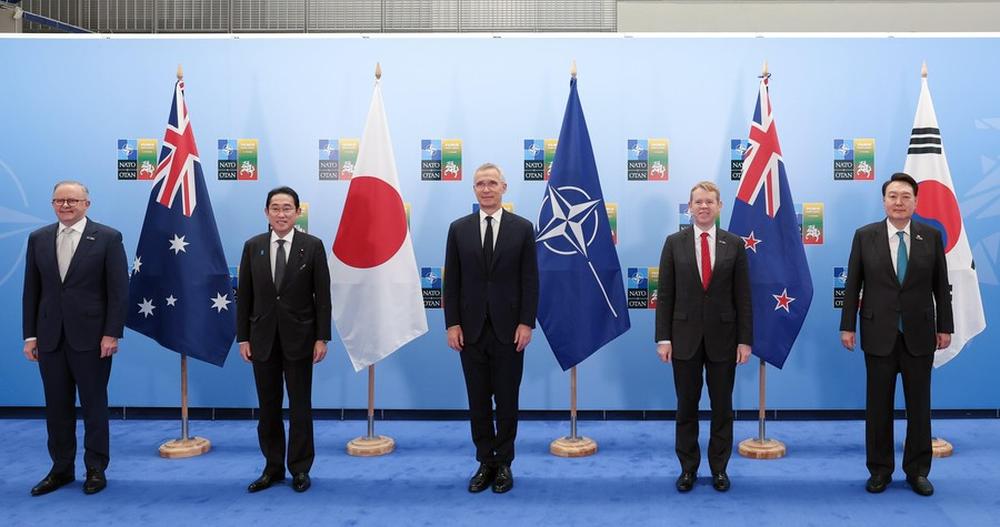

Beyond the topics that made the headlines, one could sense two paradoxes during the last NATO summit. First, the awakening of some EU countries to hard defense (courtesy of Vladimir Putin) has not so far been conducive to a consensus on stronger European defense –most EU countries now belong to the Alliance and are content with its protection. Second, while the war against Ukraine stressed the need for deterrence on the European continent, there have never been more initiatives and language related to Asia (and this happens just as the EU seems to be “pivoting” to the Indopacific too). We contend that these paradoxes can be food for thought for the Asian partners of NATO (AP4) as they increasingly interact with the Alliance.

The role of NATO for European security can be – provocatively - described as both considerable and quite limited. A bulwark against communism and Europe’s official peace insurance policy for over 70 years, it recently became the main (and fallacious) argument in the Russian rhetoric of aggression; it also became a horizon of reassurance for two EU members - Finland and Sweden - as well as for Ukraine, who hankers for an invitation to join. However, it is also limited in many regards. Even though the threat of high-intensity conflict has materialized, European security is about many more phenomena, such as the plague of terrorism, the weaponization of migration or threats to economic security, which call for political solutions rather than military action. Even on the Ukrainian theatre, NATO’s role is limited. It has delivered to its members as a provider of deterrence through the Enhanced Forward Presence & Tailored Forward Presence. Nevertheless, most weaponry and financial aid were given either bilaterally by the US and other countries or, multilaterally, by the EU. IRSEM researcher Amelie Zima considers that, as a result, the Alliance has had a “limited role but strengthened legitimacy”, a paradox further magnified by the introduction of non-defense issues such as cereal export in the agenda of the brand new Ukraine-NATO Council.

NATO’s effectiveness depends on the capacity of allies to deploy the amount of means and personnel required by the new commitments. The question of where the increased spending efforts of members, as confirmed in Vilnius, will go is very much a tug of war between national needs and the will to put capacities at disposal. To take but one example, the German “Zeitenwende”-based budgetary push has been analysed (and debunked) as mostly funding long overdue equipment replacement and modernization. Spending efforts by members thus do not necessarily amount to any effective reinforcement of NATO. More important is the issue of political cohesion : that Sweden managed to join is a relief for the Allies, but its path to integration revealed many internal disagreements, especially vis-a-vis Turkiye, and, worryingly, in terms of values and interests. Cohesion within the Alliance depends much on the White House too, and Joe Biden’s presidency helped considerably, but everyone is holding their breath (the renewal of Stoltenberg’s mandate indicating unease) until the next US Presidential election.

Among the other cleavages within NATO, there is the issue of the role of Europe in the Alliance and the coordination between NATO and the EU. In that regard, the Vilnius communiqué merely recognized the (potential) value of stronger and more capable European (but not EU) defence, only inasmuch as it was complementary and interoperable with NATO. But the test of the Ukraine war has shown that, when it came to providing ammunition or weapons, it was really about role distribution, not cooperation. Some in the EU, among which France, are now calling for a “European pillar” within NATO and warning against the risks induced by a “vassalisation” of Europe.

Where do the Asian partners stand and what should their take be on all that ? These partnerships are historically rooted in the key capacities brought in support of NATO missions (Australia and New Zealand for combat in Afghanistan; Japan for financial and logistical support); they recently diversified into the use of common standards (the Japanese horizon of 2% for defense spending) and have taken greater salience due to the rise of China, but also to the Alliance’s will to diversify into non-military threats.

That the AP4 grouping, however recurrent and symbolic in the NATO summits today, remains informal shows that the Asian partners are taking into account both the current proliferation of minilateral formats and China’s slandering of the “Asia-Pacific version of NATO”. However, the current upgrading of such partnerships underscores the conception thus encapsulated by the NATO Secretary-General : “what happens in Europe matters for Asia, for the Indo-Pacific, and what happens in Asia and the Indo-Pacific matters for Europe”. This rhetoric, which is shared by Japan and the US, is key to understanding what is at stake for the Asian partners, but also for the whole of Asia. The new NATO strategic concept not only notes that Beijing’s “stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge [our] interests, security and values”, but also that “security is global and inseparable”. That legitimates the extension of NATO’s (geographical and thematic) scope beyond deterrence in the Euro-atlantic region, to hybrid threats and situation awareness in the Pacific. There is no denying that revisionist forces are currently at play and that the rules-based order is being threatened. However, coordinating security dynamics awareness as well as responses in one another’s regions may imply aligning assessments in a performative way and possibly lumping together distinct phenomena. Lastly, it could lead to clubbing together the four Asian partners – when we know they have different, nuanced stances on security architecture in Asia. For some, the objective for the US with NATO’s current “Look and Act East” revamp is to “knit together [their] patchwork of different regional security systems into a global security architecture” and forge a “common security lexicon”.

The plan to open a liaison bureau in Tokyo illustrates the will to increase the NATO footprint into substantive engagement, beyond the mere benefits of coordinated stratcom. The question I want to raise is whether that may not end in AP4 members cutting themselves off from their Asian neighbors, or from the “ASEAN way” they have been eager to accommodate. Do symptoms of contestation of the international order necessarily call for a “global” answer - likely to alienate the Global South – and how can a global security architecture adapt to local threats (such as grey zone situations and those intertwined in regional politics)? In other words, will that not lead to a new form of “them vs. us” ?

The conundrum Europe faces today shows what happens when you invest everything in economic growth rather than in building home-grown defense capacities and in making geopolitical assessments and positioning converge. The EU did a lot in many past conflict situations to attain peace and security through a comprehensive approach to security, not unlike that of many Asian countries. However, it seems at a loss when it comes to promoting its singular vision of security and its role as a global player. Likewise, the EU has provided a lot to Ukraine, not only money but also weapons, ammunition, logistical support - not to mention the use of its economic clout through sanctions and the aid given to refugees, but it still struggles to be identified as a geopolitical actor – very much in the way it is the first investor in South East Asia, but fails to be recognized as a major political partner there. Interestingly, it was recently argued that Japan, after long advocating comprehensive and economic security approaches accommodating the objectives of development, now seemed to put emphasis on power politics and military approach, when it should be focusing on middle power diplomacy. As a result of their overreliance on NATO for security, not only have Europeans given up on building a defense industry (when it would make sense for a fully integrated economic and monetary union), but the very notion of a European defense industry was dismissed by NATO’s Secretary General. Rapprochement with NATO is obviously not wrong in itself, but in the long run, it may prove a misguided, short-term bet. The Asian partners have to be clear-eyed about the fact that, rather than proving an avenue for more defense cooperation between them, it may preclude any progress in indigenous strategic culture, let alone regionally-owned security architecture.

Dr. Marjorie Vanbaelinghem is the director of the Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM) at the Ministry of Armed Forces of France. She has a PhD and is an alumna of both the Ecole Normale Supérieure and the Ecole Nationale d’Administration. She taught at several universities, in France and Great Britain, from 2001 to 2008 before joining the diplomatic corps. She started her career at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2009 in in the strategic affairs directorate, worked in several embassies on the French diplomatic network, such as Tokyo, London and Madrid, and also served as Consul general of France in Bangalore, India before joining IRSEM, initially as deputy director. She has recently carried out research on Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. She speaks fluent English and Spanish and proficient Italian and Japanese.