Key Takeaways:

- South Korea emerged from the APEC summit with comparatively favorable trade and security agreements, including tariff relief and long-sought U.S. assent on nuclear-powered submarines and fuel-cycle capabilities.

- Yet these gains rest on fragile foundations, as implementation remains legally, politically, and strategically uncertain—and heavily dependent on continued U.S. approval.

- With the 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy revealing deep incoherence and transactional instincts toward allies, Seoul should treat post-APEC stability as provisional and plan accordingly.

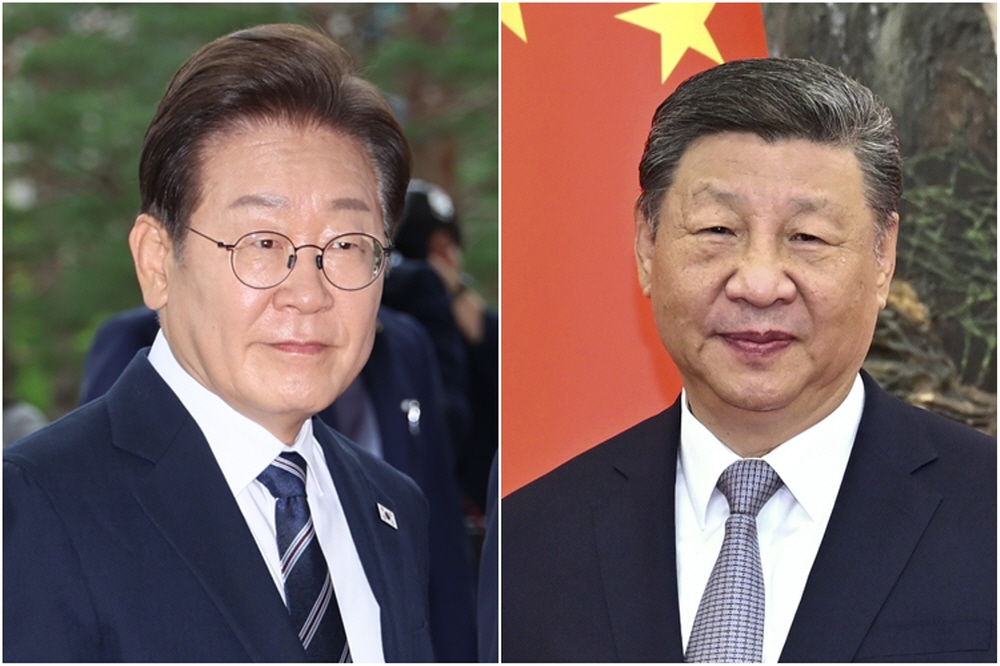

Given the circumstances, and relative to other US allies and strategic partners, South Korea can be moderately content with the current Washington-Seoul relationship. Despite a challenging timeline and demanding interlocutor, the Lee Jae-myung administration succeeded in negotiating a number of comparatively favorable economic and security/defense agreements with the Trump White House before and during the bilateral summit headlining the APEC extravaganza six weeks ago. For Trumpworld, however, six weeks is an eternity, and circumspection by South Korea is warranted. Indeed, since APEC a number of developments—especially the release of the 2025 US National Security Strategy—provide additional context by which one should evaluate the future of the new bilateral agreements intended to provide a forward-oriented foundation for US-South Korea relations. This Korea on Point contribution aims at this evaluation and concludes that Seoul should be cautious about assuming that recent outcomes will accomplish stated objectives.

Let’s Make a Deal

On the trade and commerce side of the ledger, over the

summer and early fall Washington and Seoul negotiated

a 15% basic tariff rate on US imports of South Korean goods (the same as Japan

and the European Union). This was conditioned on a contentious investment

component of the deal, in which South Korea managed to secure substantial

changes to initially infeasible US demands. Namely, instead of $350+bn of

investment by 2028 (with the US taking wildly disproportional profits and

influence over investment targets), South Korea is committed to invest $150bn

in shipbuilding over an uncertain timeline and $200bn over the coming decade or

more on other strategic industrial opportunities. This is not a huge amount

more investment than South Korean firms likely intended anyway as a part of

increased focus on the US market and de-risking from China. Moreover, South

Korea is not obligated to exceed $20bn in annual US-bound investment, thus

reducing the risk of foreign exchange volatility. Seoul also agreed to other

minor concessions, such as importing additional US-manufactured vehicles and

commercial airliners, streamlining phytosanitary import regulations,

cooperating on intellectual property rights, reducing digital services

discrimination, etc. On the whole, the Strategic Trade and Investment Deal is

not as sound as the previous KORUS FTA, but it is better

than new US arrangements with Japan or the EU.

In security and defense, Washington-Seoul discussions over

the last year have circled around the notions of alliance “strategic

flexibility” and “modernization,” which point toward greater responsibility

by South Korea for both conventional warfighting and integrated deterrence on and

around the Korean Peninsula. This complex of issues cast a shadow over the

security and defense part of the October 29 Trump-Lee meeting, with the big

news being US willingness to allow South Korea to build nuclear-powered attack submarines,

and to achieve civil reactor uranium enrichment and spent nuclear fuel

reprocessing for peaceful purposes. Both of these are long-held South Korean

goals, and getting US assent was a genuine accomplishment by the Lee

administration, although the paths toward completion of these capabilities are

long, uncertain, logistically

unclear, legally complicated, financially

and politically

fraught, and strategically

risky. There was also a diplomatic price, as Lee’s statement

announcing the submarine agreement put him on the record that South Korea acknowledges

the US expectation that they may be used to counter China—a statement likely

necessary to get Trump’s approval, but also one likely to irritate

China.

The security and defense portion of the US-South Korea

summit factsheet

also contains Seoul’s pledges to increase defense spending to 3.5% of GDP,

purchase $25bn in US defense equipment by 2030, and support US Forces Korea

with $33bn in comprehensive payments (orders of magnitude bigger than

agreed-upon amounts under the Special Measures Agreement), in addition to

numerous advancements on extended nuclear deterrence, US transfer of wartime

operational control to South Korea, North Korea policy, and other areas covered

in more detail by the annual US-South Korea Security Consultative Meeting and

Military Committee Meeting.

Well Begun Is (Still

Only) Half Done

It is tempting to look at the resolution of recent US-South

Korea negotiations and believe the Washington-Seoul relationship on solid

ground. But closer examination of US discourse since APEC shows deep currents

of complications, uncertainties, incoherence, and differing interests that

represent risks to the hard-fought stability that South Korea perceives in its

relations with the US post-APEC.

To begin with the nuclear-powered submarines, initial

Washington-Seoul misalignment

(misunderstanding? miscommunication?) on construction location, reactor

design, fuel sourcing, and other technical issues has subsided in favor of South

Korea building the boats in South Korea using an indigenous reactor design and

fuel. Yet huge complications and uncertainties remain for both Washington and Seoul.

As the timeline will consequently be long, this means that Seoul’s

nuclear-powered submarine acquisition will depend on continued US approval for

the foreseeable future. Heightening that risk is a connected issue, namely that

the Lee administration has tried to downplay

(even walk back) Lee’s affirmation that South Korean nuclear-powered attack

submarines could be deployed to counter China, a retraction that Washington has

admonished.

The path

to acquiring capabilities for uranium enrichment and spent nuclear fuel reprocessing

is even more fraught, requiring

numerous legal/regulatory changes beyond revision of or addenda to the US-South

Korea Agreement for Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation (the “123 Agreement”). There

are many non-proliferation obstacles that could be leveraged by US

congressional and bureaucratic opponents of South Korea enriching uranium and closing

the nuclear fuel cycle. President Trump and his senior officials have given

their approval, but if they become disengaged (or lose office) in providing

support to the initiative, Seoul’s efforts could stall.

Beyond these headline items, the post-APEC period has already

seen Washington-Seoul differences on the approach to Pyongyang (including a Lee

administration terminology

shift softening language on North Korean denuclearization, unappreciated

by Washington), the prospect

of temporarily reducing US-South Korea combined military exercises (which some

Lee administration officials advocate, occasioning US pushback),

the procedure

for reversion of wartime operational control of the South Korean military

under the Combined Forces Command (which the Lee administration wants on a

timeline, while the US insists on a conditions-based process), and the desirability

of proposed

projects for South Korean investment into US energy infrastructure (an

ostensible part of South Korea’s possible investment commitments).

The biggest question mark for the US-South Korea alliance

post-APEC is the same one facing all of Washington’s allies: what is the

meaning of the new US National Security Strategy (NSS)?

It is difficult to assess the post-APEC US-South Korea alliance in light of the

NSS because the document is utterly

inconsistent, arguing for and against: US primacy, great power competition,

Asia versus the western hemisphere as the focus of US power, and respect for US

allies, inter alia. The NSS is

somehow both transactional and deeply ideological, imperialist and

isolationist. The only constant is disdain for multilateralism and the

international rules-based order (an external reflection of the US’s domestic

drift to authoritarianism), underpinned by a MAGA ethos ultimately viewing

allies as instruments of US power.

Both the inconsistencies and constants of the NSS should worry South Korea. North

Korea does not merit a single mention in the NSS, despite the North Korean threat to the US, South Korea, and

Japan, as well as the document’s plain assertion of US interest in countering

any country representing a risk inside the first island chain. China is treated

primarily as an economic problem rather than a security concern, despite the NSS arguing for preventing the emergence

of a rival to US hegemony in any region, including Asia. The NSS toggles back and forth between Asia

and the western hemisphere as the key region requiring Washington’s attention

and resources. Allies are instructed to be more capable of and responsible for

their own security, yet are unsupported with respect to becoming more

autonomous. Moreover, they are simultaneously beggared by US trade policy.

More worrisome still is the NSS’s description of and prescription for Europe. The document’s open

call for US-backed subversion of Europe’s centrist-led democracies (in favor of

far-right ethno-nationalist parties), as well as of the European Union as an

entity, demonstrates clear metastasis of US domestic authoritarianism and

Christian nationalism into the undermining of both the international rule-based

order and sovereign liberal democratic political choices of other states. This

type of behavior by a powerful ally should be profoundly unsettling to Seoul,

both because it destroys multilateralism and the international rules-based

order in which middle powers thrive, and because it indicates that the US is

willing to act neo-imperialistically. South Korea already has revisionist

neo-imperial China in its neighborhood; it does not need a revisionist

neo-imperial US ally in addition.

Past Performance Is

No Guarantee of Future Results

The NSS is unsuited

as a tool for divining specific future US policy, but it is very helpful in

revealing general US unreliability. The NSS

is a psychopathological profile of Trump administration schizophrenia—a

competing mash-up of primacists, prioritizers, restrainers, neo-isolationists,

neo-imperialists, MAGA populists, Christian nationalists, and various flavors

of crackpot overseen by a mercurial, corrupt, venal executive. There is no consistent

strategic core, and thus no coherence. Therefore also no reliability.

To wit, after months of export controls on NVIDIA H200 GPU

sales to China (ostensibly the US’s only near-peer rival), on December 8 the US

Justice Department indicted

numerous suspects on violating the ban. The following day, Trump announced

through social media that NVIDIA would

be allowed to sell China the H200

chips, which are critical for advanced artificial intelligence training that

the US government claims should be restricted for national security reasons. It

is nearly impossible to understand the strategic logic of these developments.

If you are a country—such as South Korea—that faces US-imposed foreign-direct

product rule restrictions on semiconductor and semiconductor equipment exports

to China, how do you understand this US reversal? Simply put, US policy can

change at a whim.

Likewise, even as the US—e.g., in the NSS—claims that allies should increase their own contribution to

deterrence, including pushing back against China, the Trump administration has barely

supported Japan after new prime minister Sanae Takaichi stated the obvious

fact that a Taiwan Strait crisis would represent a potentially existential risk

for Japan, to which China responded with

rhetorical abuse and military escalation. How ought Japan and—mutatis

mutandis—South Korea understand this US reversal? Again, US policy can change

at a whim.

For South Korea, there is seemingly stability in the Washington-Seoul relationship: difficult agreements are now signed, the upcoming 2025 US National Defense Strategy supposedly refers to South Korea as a model ally, etc. But with all things Trump, one’s place in the sun today does not imply favor tomorrow. The question is, what should South Korea do about it?

Mason Richey is professor of international politics at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (Seoul, South Korea), president of the Korea International Studies Association (KISA), and Editor-In-Chief of the Journal of East Asian Affairs. Dr. Richey has also held positions as a POSCO Visiting Research Fellow at the East-West Center (Honolulu, HI), DAAD Scholar at the University of Potsdam (Germany), and Senior Contributor at the Asia Society (Korea branch). His research focuses on European foreign and security policy, US foreign policy in the Indo-Asia-Pacific, and cybersecurity. Recent scholarly articles have appeared (inter alia) in Australian Journal of International Affairs, Asian Survey, Political Science, Journal of International Peacekeeping, Pacific Review, Asian Security, Global Governance, and Foreign Policy Analysis. Shorter analyses and opinion pieces have been published in War on the Rocks, Le Monde, the Sueddeutsche Zeitung, and Forbes, among other venues. Dr. Richey is also co-editor of the volume The Future of the Korean Peninsula: 2032 and Beyond (Routledge, 2021), and co-author of the US-Korea chapter for the tri-annual journal Comparative Connections (published by Pacific Forum). He is also a frequent participant in a variety of Track 1.5 meetings on Indo-Asia-Pacific security and foreign policy issues.