- #China-US Competition

- #Economy & Trade

- #US Foreign Policy

►Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which consists of 14 member countries, is the centerpiece of the Biden Administration’s economic strategy in the region. IPEF is not a traditional trade agreement but a platform for discussion between the United States and partners in the region on shared economic concerns. Its agenda is organized into four pillars: trade, supply chain resilience, clean energy and infrastructure, and tax and anti-corruption.

►The following paper discusses what IPEF is, the challenges the US will have to face, China’s potential reaction, and implications for Korea’s future contribution to IPEF.

What is the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF)?

The United States is a Pacific power, but it is not an Asian country. As a result, the United States has to prove its commitment to the Asian region. For U.S. partners, maintaining a military and diplomatic presence in the region is simply not enough. The United States must be involved in the region as an economic player—for the benefit of the region as well as the United States. Given that the Indo Pacific represents about half of global trade, population, and GDP, it is essential for the U.S. to remain engaged in the region.

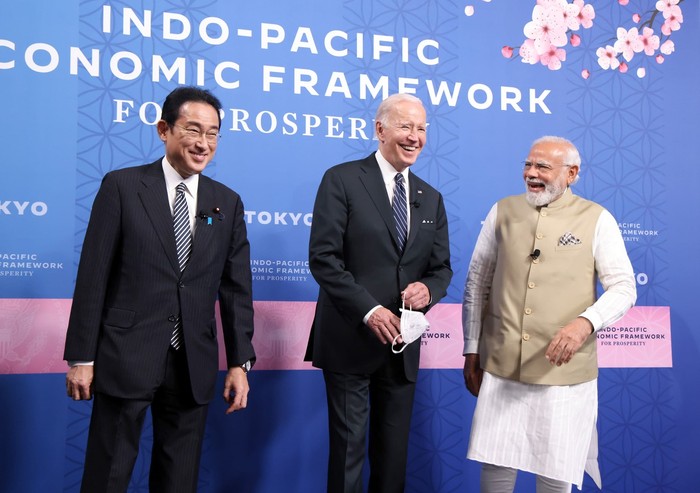

The recently launched Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is the centerpiece of the Biden Administration’s economic strategy in the region. IPEF is not a traditional trade agreement but a platform for discussion between the United States and partners in the region on shared economic concerns. Its agenda is organized into four pillars: trade, supply chain resilience, clean energy and infrastructure, and tax and anti-corruption.

IPEF’s initial membership totals 14 countries, including the United States. While theoretically its membership could expand and become more global, it will likely remain unchanged for the foreseeable future. IPEF represents a broad cross-section of nations in the Indo-Pacific region, and its current membership serves as a good starting point.

Ultimately, IPEF will be judged by whether it can advance regional economic rules and norms that make the region more prosperous and more stable. The initial ministerial-level discussions will take place in July. These discussions will outline the parameters of future negotiations. Only then will actual negotiations take place. It will likely be at least 12 to 18 months before we see any tangible results.

For the United States, IPEF complements its arrangements with other regions. For example, the United States has the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) with the EU and the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP) with Latin America. Of course, there are also the G7 and the G20, and bilateral arrangements with Korea, Japan, and other partners. While these are different initiatives, they are not mutually exclusive, and the United States is trying to make them broadly consistent in its agenda and objectives. In the case of the TTC, its approach is slightly different from IPEF in that EU can be considered a single entity (despite the fact that it represents multiple European nations) and, therefore, trade negotiations can be conducted in a bilateral manner. Negotiations will be more complicated in the case of IPEF because of the number of countries involved, each of which has a different perspective on the topics on the IPEF agenda. Moreover, the TTC is oriented more towards technology issues such as protecting and promoting critical technologies, while IPEF covers a broader set of economic rules and standards.

China’s Potential Reaction

China has publicly expressed its opposition to IPEF, calling it an effort to “contain” China. Beijing may try to persuade other partners in the group not to participate, it may try to actively slow down negotiations, or it may set up its own separate initiative to counter IPEF. There appears to be concern among Koreans that China will engage in coercive acts in response to Korea joining IPEF. This would not be unprecedented, but it would be an overreaction. IPEF is not a policy to contain China, nor is it a hostile act. It is an initiative designed to compete with China. IPEF is not a powerful enough arrangement to contain a country like China. Rather than thinking about how to retaliate against IPEF, China should think about ways to compete with IPEF.

Korea’s Role in IPEF

The benefits for Korea for participating in IPEF are more indirect than direct. In terms of rules, norms, and standards on trade, labor conditions, environmental standards, and digital economy, Korea already operates according to high standards. Of course, the U.S. would like to advance these standards further in certain areas. But the United States’ expectation is for Korea to persuade a wide group of partner countries, such as Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and other ASEAN countries, that the United States’ preferred rules and standards are best for them. If the United States and Korea can persuade those countries to accept higher standards and stronger rules and norms in economics, it will create more stable and prosperous economies, which will lead to more export opportunities, better regional rules, and greater efficiency.

Concurrently, Korea can play a useful role by offering ‘friendly advice’ to the United States to provide members of IPEF with greater market access, as well as more financial support for capacity building, infrastructure development, or the clean energy transition. In other words, Korea could play a useful role in persuading partners in Southeast Asia and South Asia about the benefits of standards and norms shared by the U.S. and Korea and, at the same time, play an advisory role to the United States with the goal of providing more tangible benefits for these countries.

Challenges for IPEF

Following the United States’ withdrawal from the TPP in 2017, Asian partners experienced a kind of trauma that still shapes their view of U.S. economic engagement in the region. While these concerns may spill over to IPEF, the U.S. domestic political risks associated with IPEF are much lower than the risks that accompanied TPP, because IPEF is not a traditional trade agreement. The Biden Administration has made clear that it does not intend to seek political approval from Congress for IPEF.

The problem with this is that it raises questions about IPEF’s durability. If IPEF were a traditional trade agreement ultimately approved by legislatures in the United States and other countries, it would become embedded in domestic law. Based on the Biden Administration’s current approach, IPEF is missing that element because it won't need approval from Congress. If the United States elects a new president in 2024, he or she may simply lose interest and decide to walk away from IPEF. Another concern is that the Biden Administration is unwilling to provide greater U.S. market access to IPEF members, as it would in a traditional trade negotiation. Again, Korea can play an important role by advising the United States to give something tangible in return for these members adopting higher standards in various areas including labor, environment, agricultural regulations, competition, and digital trade.

With 14 countries having joined the initiative at its launch on May 23, the Indo Pacific Economic Framework is off to a good start. Despite concerns about its durability and just how much it will actually advance U.S.- and Korean-preferred rules, norms, and standards, it is a good platform with a useful agenda and a broad group of countries that can shape the initiative into something beneficial for the region.

Matthew P. Goodman is senior vice president for economics and holds the Simon Chair in Political Economy at CSIS. The CSIS Economics Program, which he directs, focuses on international economic policy and global economic governance. Before joining CSIS in 2012, Goodman served as director for international economics on the National Security Council staff, helping the president prepare for global and regional summits, including the G20, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and East Asia Summit. Prior to the White House, Goodman was senior adviser to the undersecretary for economic affairs at the U.S. Department of State. Before joining the Obama administration in 2009, he worked for five years at Albright Stonebridge Group, where he was managing director for Asia. From 2002 to 2004, he served at the White House as director for Asian economic affairs on the National Security Council staff. Prior to that, he spent five years at Goldman, Sachs & Co., heading the bank’s government affairs operations in Tokyo and London. From 1988 to 1997, he worked as an international economist at the U.S. Treasury Department, including five years as financial attaché at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo. Goodman holds an M.A. in international relations from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) and a B.Sc. in economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He is a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations and chairman emeritus of the board of trustees of the Japan-America Society of Washington, D.C.